December 21, 2015

New Blog!

I have a new blog called Detroit Urbanism. It's about the way history shapes our maps and built environment in both the city of Detroit and its suburbs. Posts on the new blog will be similar to the last few ones that I have posted on Corktown History, and a whole new site seemed more appropriate home for future articles. Click here to read and enjoy!

October 23, 2015

The Origins of Eight Mile Road

Inspired by the 200th anniversary commemoration of the survey of Michigan and surveyor Joseph Fenicle's April 2015 article on the subject, I've spent the last couple of months researching the field notes of the original surveyors (scans of which are available on SeekingMichigan.org) and the Territorial Papers of the United States in order to understand how our road system and municipal boundaries in Metro Detroit took the shapes that they did. I've been especially interested in the establishment of Eight Mile Road, because this October 24th marks exactly 200 years since the first surveyor's marks were left upon it.

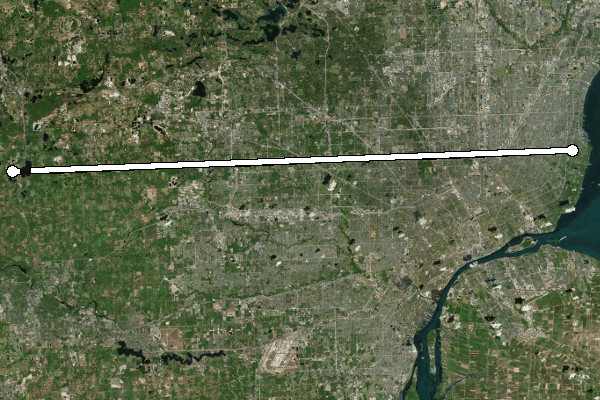

When Michigan was part of the Northwest Territory, the Federal government desired to sell and settle as much land as possible. This necessitated a systematic, economical method of parceling out the land, which we now call the United States Public Land Survey System. Land was divided into townships measuring six miles by six miles, then townships were later subdivided into square mile sections. The first step was establishing vertical and horizontal axes. The east-west axis upon which virtually all land in Michigan (aside from the old French claims and their extensions) was divided is Michigan's Baseline. When land was surveyed and settled, roads tended to be built on township and section lines. Roads have been built on the Baseline throughout the state, and in the Detroit area, 45 miles of it is called Eight Mile Road.

Eight Mile Road.

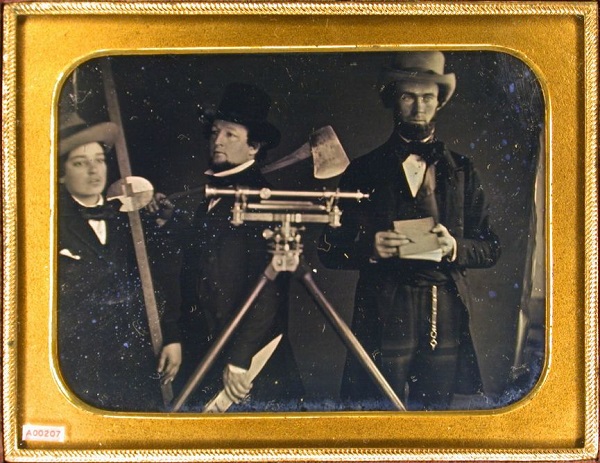

On April 18, 1815 surveyor Alexander Holmes entered into a contract with Edward Tiffin, Surveyor General of the Northwest Territory, to establish the Baseline. He was also to survey a portion of the 96 townships that had been set aside to be divided and used as payment to soldiers and officers who had served in the Revolutionary War. Holmes received permission to give half the contract to his surveyor brother, Samuel. The contract stipulated a payment of $2.50 per mile of township and section line surveyed, and $3.00 per mile of baseline surveyed. Each surveyor had to pay his own crew out of these funds. They measured their path with a Gunter's chain, cut down trees that were in their line of sight, and planted posts every half mile along their path.

Surveyors and their tools, circa 1850. (Source.)

Alexander Holmes had attempted to begin running the Baseline in May of 1815, but was driven back to Detroit by Indians who disagreed over the description of boundaries given in the 1807 Treaty of Detroit, which granted most of southeast Michigan to the U.S. government. It's not known whether Holmes actually reached the Baseline then, and if so, how much work he accomplished, or if any of that work might coincide with today's Eight Mile Road.

Why There?

Why was the Baseline drawn where it was? Various proposals were considered before surveying began. Surveyor General of the United States Josiah Meigs suggested a baseline "beginning at Detroit, running from thence ... due west" in March of 1815. But Edward Tiffin proposed a scheme where the Baseline would be run north of Detroit, and Meigs approved. Tiffin's contract with Holmes simply instructs him to run "a true base line due West from a point above Detroit". For a long time I believed that the location of Michigan's Baseline was tied with the Point of Beginning in Woodward's plan of Detroit--Ford Road, which coincides with a section line in the survey system, appears to almost line up with Michigan Avenue, which is an arterial road in Woodward's plan. This appears to be only a coincidence.

Ford Road and Michigan Avenue are misaligned by only 300 feet, but

the Woodward Plan probably did not influence the survey of Michigan.

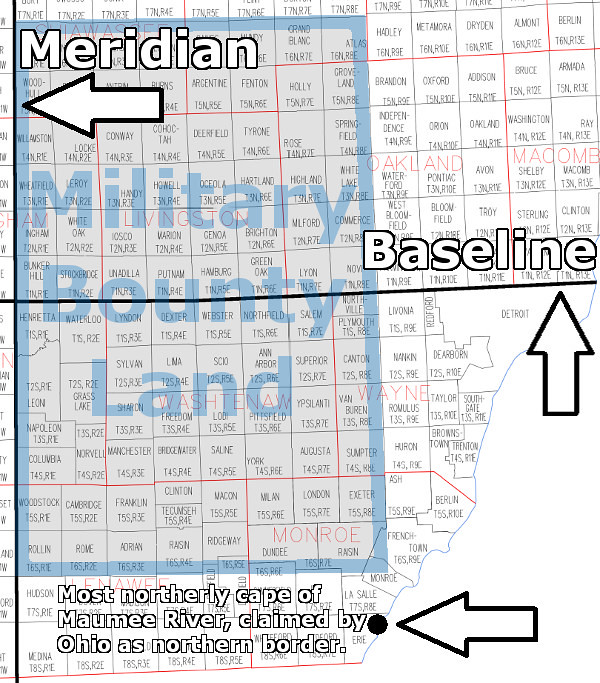

The real reason had to do with the 96 townships of military bounty land mentioned earlier. This area was to measure eight townships wide by twelve townships long. The western border was to rest on the Michigan Meridian, the north-south axis of the survey. The Baseline was to run directly through it, putting 48 townships north of the Baseline and 48 townships south of it. The surveyors needed to ensure that this land in no way interfered with Ohio's land claims. Ohio's northern border had not yet been surveyed, but it was supposed to terminate at the Maumee River Bay, possibly as far as the northernmost cape within the bay, well within present-day Erie Township, Michigan.

Surveyor Benjamin Hough was contracted to survey the Michigan Meridian, which coincided with the western border of land ceded by Native American tribes in the 1807 Treaty of Detroit. According to the treaty, the border began at Fort Defiance, Ohio and ran due north. Hough first traveled to Maumee Bay, and on May 27, 1815 observed the position of the sun at noon and calculated his latitude to be 41°47'07" North. (He made this observation at the northernmost cape in Maumee Bay, apparently as a means of extreme caution. Ohio's actual border, surveyed the following year, began 3.7 south of this point.) Hough used this data to determine how far north the military bounty land should lie, and then rounded this figure so that there would be a whole number of townships between Fort Defiance and the military reserve. Hough calculated that Fort Defiance should be at the southwest corner of the 13th township south of the Baseline, and that the military land would begin seven townships north of there.

Thirteen townships measuring six miles on a side is 78 miles. Michigan's Baseline and Eight Mile Road exist where they do because the center of the military bounty land needed to be 78 miles north of Fort Defiance in order for that land to lie completely outside of the State of Ohio.

A monument at Fort Defiance marks the beginning of the Michigan Meridian.

The Survey Begins

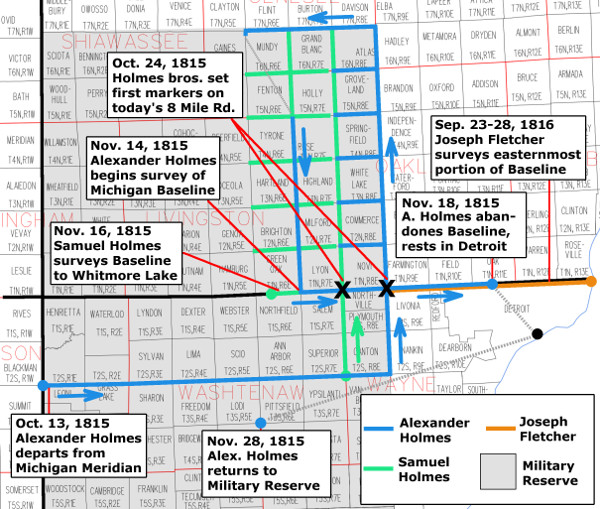

Alexander Holmes teamed up with Benjamin Hough, who began his work at Fort Defiance on September 29, 1815. The two apparently traveled north together and planned to split up once they reached the calculated position of the Baseline. Instead, they were blocked by the impassable and flooded Grand River in what is now Leoni Township. Rather than meticulously measuring a path around the flooded area using a surveying technique called "meandering," Holmes backtracked slightly and began surveying east on a line twelve miles south of and parallel to the Baseline.

In the vicinity of Detroit, Alexander Holmes met up with his brother, Samuel, who was waiting for him with additional provisions and assistants as planned. On October 23rd 1815 they set north simultaneously from the east-west line that Alexander had surveyed. Alexander's team worked north on what is now Haggerty Road, which was originally intended to be the western border of the 96 military reserve townships. Samuel's team surveyed north on what is now Napier Road.

The field notes taken by both teams indicate that they reached the Baseline and set their marks on October 24th. The spot where Alexander Holmes drove a post into the ground is preserved by a modern surveyor's marker, protected by a cast iron cover and marked with a white X in the median on Eight Mile Road just west of I-275. It still denotes the legal corner between present-day Farmington Hills, Novi, Northville Township and Livonia. Everyone interested in the history of Farmington knows that Arthur Power was the first white settler in the township, but the surveyors came first--clearing a path through the forest and leaving their marks almost a decade before Arthur Power arrived.

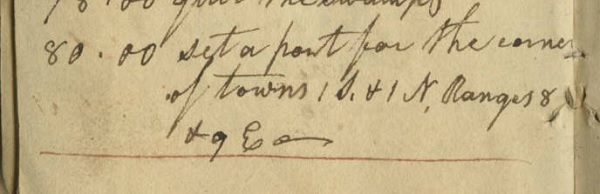

Excerpt from Alexander Holmes' field notes when he

planted a post at today's Eight Mile Road and Haggerty.

Image courtesy of the Archives of Michigan.

The exact spot where surveyor Alexander Holmes set his

first marker on Michigan's Baseline on October 24, 1815.

This cast iron cover protects a modern surveyor's mark, set

over the spot first marked by Alexander Holmes 200 years ago.

"Mommy, why is that man taking pictures of the street?"

Six miles west of Alexander's mark, the post Samuel planted on the same day is similarly preserved, and serves as the corner of Novi, Lyon Township, Salem Township, and Northville Township. Who is to say which brother arrived at the Baseline first?

After several weeks of hacking township borders through swamps and forests, Alexander's team again reached the Baseline, on November 14th. There they set the third post on the line, which is now the southwest corner of the City of South Lyon. From there, Alexander began to survey the Baseline toward the east. Although other teams may have surveyed portions of the Baseline in Jackson County, this is the first surveyor's line drawn on the Baseline where it coincides with Eight Mile Road. Well, almost... After reaching Samuel's post at today's Napier Road, he found that he had reached it 594 feet too soon, and had to resurvey that six mile segment from east to west. (Townships were supposed to be surveyed so that any deficiencies would lie on their west and north borders--this line was resurveyed so that the deficient mile would appear on the western edge of Lyon Township.)

Samuel Holmes reached the South Lyon post and then began surveying the Baseline west on November 16th. After a few miles he ran into Whitmore Lake. Rather than meander around the 677-acre lake, he left the Baseline to continue dividing townships south of the area.

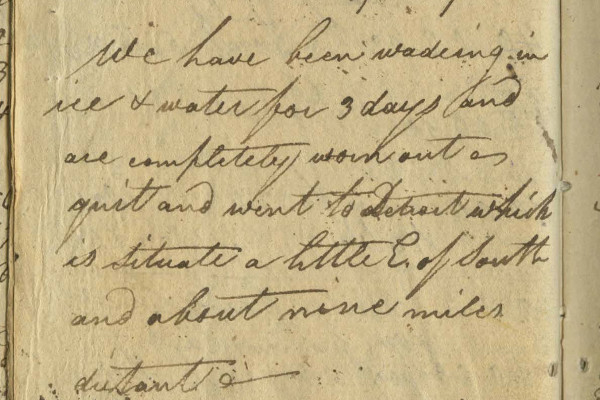

Meanwhile, Alexander Holmes continued east along the Baseline, all the way to what is now the Ferndale-Detroit border. After setting a quarter section post one half mile east of today's Livernois Ave. on November 18th, he wrote in his field notes: "We have been wading in ice water for three days and are completely worn out -- quit and went to Detroit which is situate [sic] a little E. of South and about nine miles distant."

Excerpt from the field notes of Alexander Holmes, November 18, 1815.

Image courtesy of the Archives of Michigan.

The team rested in Detroit, hoping that the swamps would freeze enough to allow the surveyors and their horses to walk across their surface rather than slush through them. Alexander Holmes returned to the field nine days later, but did not continue the Baseline. Samuel Holmes, however, did reach the western side of Whitmore Lake in December. He surveyed the 1.3 miles of the Baseline on the other side of the lake, including the point that is considered the western terminus of Eight Mile Road. He continued the line six more miles west, but the field notes are crossed out and his work was evidently redone.

Finishing the Job

The remainder of the Baseline that coincides with Eight Mile Road was surveyed the following year by Joseph Fletcher. He began at the post established by Alexander Holmes at today's Haggerty Road on September 23rd, 1816. From there he headed east, resurveying Holmes' work. Fletcher reached Lake St. Clair five days later. In a letter to Edward Tiffin, he wrote:

"I ... proceeded agreeable to my instructions to the base line, the line being very badly blazed. I was obliged to trace it with the compass on examination found I was not authorised by my instructions to vary from the line already run by Mr. Holmes only in measurement. I then proceeded with the line to the western border of lake St. Clair....

"... the lines vary very much from the field notes and plats--and the lines being indifferently blazed--renders it one of the most disagreeablest jobs I ever was engaged in..."

Eight Mile Road's eastern terminus in St. Clair Shores,

about one and a half miles west of Lake St. Clair.

Fletcher complained that the Baseline in this area runs slightly to the northeast by 2°40'. Here is the reason why that is. Back at Fort Defiance, Benjamin Hough carefully observed the North Star in order to calculate the difference between true north and magnetic north. He found the deviation to be 4°39' east. Following this deviation worked very well in the beginning, but that observation became less accurate the farther the surveyors moved from Fort Defiance. Additional astronomical observations should have been made to update the proper deviation from magnetic north, but the surveyors were suffering many hardships and running out of time. Alexander Holmes simply pressed on to get the job done. After Fletcher finished the eastern portion of the Baseline following to Holmes' path, he realized that running range lines according to true north would result in rhombus-shaped townships and sections. In order to maintain squareness and consistency, he ran his lines perpendicular to the Baseline. This is why our major roads and municipal borders in Metro Detroit all appear slightly skewed on a map aligned to true north.

Despite these inaccuracies, the imposition of a rectangular grid on the forested surface of a spheroid planet two centuries ago is an impressive human achievement.

This obelisk in Farmington Hills close to Eight Mile Road is part

of sculptor David Barr's Coasting the Baseline series.

Barr passed away on August 28, 2015.

"Surveyors exhibited courage, determination, integrity and ingenuity in the heroic feat of measuring Michigan from 1815-1853. Their work resulted in global implementation of innovative methods of land measurement and ownership. The history of the surveying of the Base Line reveals the collision of four contrasting concepts of property: Native American, European Aristocratic, Colonial American, and Jeffersonian. From this emerged a new uniquely American set of principles which profoundly shaped our landscape, laws, and way of life."

April 1, 2015

Moving On

I became a Corktown resident ten years ago today. My first address in the neighborhood was a large Victorian house that had been divided into apartments. Since then I have had three other Corktown addresses--on Wabash St., Ash St., and Bagley Ave. Most of the years of my adult life have been spent here.

1368 Pine Street, my first Corktown residence.

Today I am sad to announce that I will be moving away. No, this isn't world's lamest history-blog-related April Fool's Day prank. Although I've never had a reason to discuss personal information here, I think I do owe an explanation for my leaving. It has nothing to do with Detroit's infamous quality of life issues (crime, insurance costs, or worse). I think I came well equipped to handle those.

My problem is that I'm extremely sensitive to noise, especially low frequencies. Corktown is not only an urban neighborhood at the center of a major metropolitan region, but it's a nighttime entertainment district. Noises don't necessarily have to be at a high decibel level in order to cause severe discomfort for me. Sometimes when I am disturbed by a band playing in a bar close to my house, my girlfriend will barely be able to hear the music at all. I've discussed noise with my neighbors, but they see it as just an inconvenience and not a cause of extreme discomfort or psychological stress. Now, the last thing the internet needs is another blogger diagnosing himself with some sort of medical issue via Google--but having said that--there is an unmistakable overlap between my experience and the symptoms of conditions like hyperacusis, misophonia, and selective sound sensitivity syndrome.

So, Corktown, "it's not you, it's me." I don't want to be the prude who goes around the neighborhood wagging his finger at people and telling them to turn their music down. I think it will be wisest for me to peacefully bow out.

It will be a few more weeks until the actual move, but in a lot of ways I'm regretting it already. I've never lived anywhere else where I knew as many of my neighbors as I do here. I've never carved out a niche for myself or felt more productive and useful as I do when practicing my abilities as a researcher of the history of Detroit's oldest neighborhood. And it goes without saying that Corktown's architecture and walkability will be very sorely missed.

After carefully considering other communities in southeast Michigan, my girlfriend and I ultimately chose a place in Farmington. As my neighbor Jon asked, "Farmington?!? Why!?!" Our basic criteria were that the new house had to 1.) be old (pre-WWII), 2.) be affordable, and 3.) located in a city with a walkable downtown, but 4.) not in an area that is a major nighttime party destination. We found a cottage built in 1935 on a wooded acre in Farmington Hills just one mile from downtown Farmington. There is one neighbor on the north side, a daycare to the south, and undeveloped forest to the east. We got a good deal because the house needed a total rehab--the asbestos-wrapped ducts needed to be removed, and it needed a new roof, furnace, plumbing and electrical systems. The kitchen and bathroom have been gutted completely, and I've been working at the house every weekend for five months--plus using up all of my vacation time at work--to get the job done on time. As I write this, the rough building, plumbing and electrical work has been approved and the drywall is just barely up (and scheduled to be finished this weekend). The bathroom and kitchen should be functional just in the nick of time for our scheduled move-in. In the summer I will remove the aluminum siding and repaint the original cedar lap siding beneath.

The Harold and Adaline Jamieson Cottage, built in 1935.

Farmington Hills, Michigan.

In addition to the house itself being a good find, there is a lot to like about Farmington/Farmington Hills. They appear to have a very active local history community and take a lot of pride in their historic architecture. The City of Farmington's Vision Plan is right-on as far as urbanism and walkability are concerned. And Farmington is where architects Wells D. Butterfield and his daughter, Emily Helen Butterfield--the designers of a previous home of mine settled and continued to work when they left Detroit.

This isn't the final entry for this blog--I have a few more research ideas that I'd like to work out. There is no need for me to start a blog about Farmington's history, which is already well-researched--but I do have a vague idea for a new website that combines history, maps, and architecture. The concept still needs some work.

One final note--sometimes a few local blogs will highlight anecdotes of Detroit city residents expressing hostility to newcomers. Maybe that happens occasionally. But my own experience of moving into the city after only having spent a small part of my childhood here has been overwhelmingly positive. The lifelong Detroiters I've met in Corktown and elsewhere are especially tolerant, friendly, and agreeable people. If you move here, I believe you will feel very welcome.

1368 Pine Street, my first Corktown residence.

Today I am sad to announce that I will be moving away. No, this isn't world's lamest history-blog-related April Fool's Day prank. Although I've never had a reason to discuss personal information here, I think I do owe an explanation for my leaving. It has nothing to do with Detroit's infamous quality of life issues (crime, insurance costs, or worse). I think I came well equipped to handle those.

My problem is that I'm extremely sensitive to noise, especially low frequencies. Corktown is not only an urban neighborhood at the center of a major metropolitan region, but it's a nighttime entertainment district. Noises don't necessarily have to be at a high decibel level in order to cause severe discomfort for me. Sometimes when I am disturbed by a band playing in a bar close to my house, my girlfriend will barely be able to hear the music at all. I've discussed noise with my neighbors, but they see it as just an inconvenience and not a cause of extreme discomfort or psychological stress. Now, the last thing the internet needs is another blogger diagnosing himself with some sort of medical issue via Google--but having said that--there is an unmistakable overlap between my experience and the symptoms of conditions like hyperacusis, misophonia, and selective sound sensitivity syndrome.

So, Corktown, "it's not you, it's me." I don't want to be the prude who goes around the neighborhood wagging his finger at people and telling them to turn their music down. I think it will be wisest for me to peacefully bow out.

It will be a few more weeks until the actual move, but in a lot of ways I'm regretting it already. I've never lived anywhere else where I knew as many of my neighbors as I do here. I've never carved out a niche for myself or felt more productive and useful as I do when practicing my abilities as a researcher of the history of Detroit's oldest neighborhood. And it goes without saying that Corktown's architecture and walkability will be very sorely missed.

After carefully considering other communities in southeast Michigan, my girlfriend and I ultimately chose a place in Farmington. As my neighbor Jon asked, "Farmington?!? Why!?!" Our basic criteria were that the new house had to 1.) be old (pre-WWII), 2.) be affordable, and 3.) located in a city with a walkable downtown, but 4.) not in an area that is a major nighttime party destination. We found a cottage built in 1935 on a wooded acre in Farmington Hills just one mile from downtown Farmington. There is one neighbor on the north side, a daycare to the south, and undeveloped forest to the east. We got a good deal because the house needed a total rehab--the asbestos-wrapped ducts needed to be removed, and it needed a new roof, furnace, plumbing and electrical systems. The kitchen and bathroom have been gutted completely, and I've been working at the house every weekend for five months--plus using up all of my vacation time at work--to get the job done on time. As I write this, the rough building, plumbing and electrical work has been approved and the drywall is just barely up (and scheduled to be finished this weekend). The bathroom and kitchen should be functional just in the nick of time for our scheduled move-in. In the summer I will remove the aluminum siding and repaint the original cedar lap siding beneath.

The Harold and Adaline Jamieson Cottage, built in 1935.

Farmington Hills, Michigan.

In addition to the house itself being a good find, there is a lot to like about Farmington/Farmington Hills. They appear to have a very active local history community and take a lot of pride in their historic architecture. The City of Farmington's Vision Plan is right-on as far as urbanism and walkability are concerned. And Farmington is where architects Wells D. Butterfield and his daughter, Emily Helen Butterfield--the designers of a previous home of mine settled and continued to work when they left Detroit.

This isn't the final entry for this blog--I have a few more research ideas that I'd like to work out. There is no need for me to start a blog about Farmington's history, which is already well-researched--but I do have a vague idea for a new website that combines history, maps, and architecture. The concept still needs some work.

One final note--sometimes a few local blogs will highlight anecdotes of Detroit city residents expressing hostility to newcomers. Maybe that happens occasionally. But my own experience of moving into the city after only having spent a small part of my childhood here has been overwhelmingly positive. The lifelong Detroiters I've met in Corktown and elsewhere are especially tolerant, friendly, and agreeable people. If you move here, I believe you will feel very welcome.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)