The Detroit Athletic Company has sold Detroit sports memorabilia one block from the former Tiger Stadium site since 1985. Behind the facade's white stucco lie two Victorian-era buildings constructed twelve years apart. Together they originally consisted of three ground-floor commercial spaces with two apartments above. The histories of each of the commercial spaces are detailed separately below.

526 (1740) Michigan Avenue

The east (right) half of the building, originally addressed as 526 Michigan Avenue, was the first to be built.

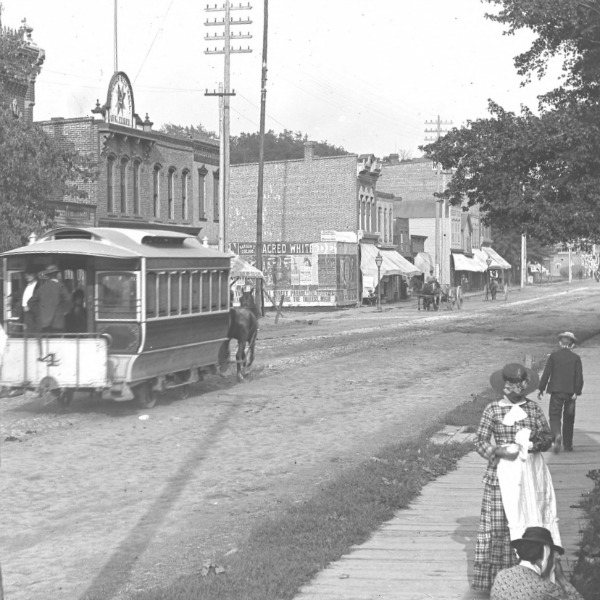

| Above: Michigan Avenue west of Harrison, some time between 1881 and 1884. (Courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library) Below: The same block as it appears today. The west (left) half of the store had not yet been built when the 1880s photos was taken. |

The permit to construct this building was issued May 24, 1878. The following day the Detroit Free Press noted, "A brick building for a store is to be built at the corner of Harrison and Michigan avenues, the excavation for the cellar having been already made." The owner was Horace M. Dean of the interior decorating firm Deans Brow & Godfrey.

The building almost didn't survive one year. On the night of February 14th, 1879, Frederick Steben of 112 Harrison Avenue saw a fire inside of the store and ran to the Trumbull Avenue police station to sound the fire alarm. Fire Engine Company No. 8 arrived within minutes and extinguished the flames. Police Officer John Martin, who accompanied Steben back to the store, discovered several partially burned piles of wood shavings saturated with kerosene inside, suggesting arson.

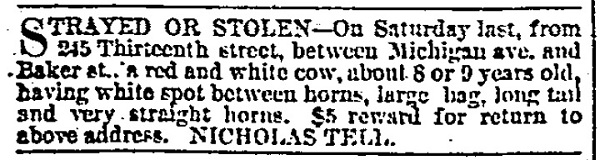

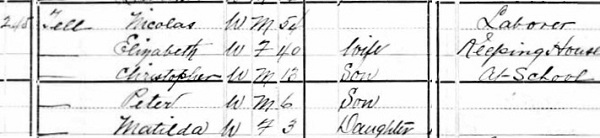

Suspicion fell upon the building's tenant, picture framer Alexander M. Kolakosky, whose merchandise on the premises was insured. He was arrested and subsequently examined in Police Court on February 25th and March 7th. Testimony was delivered by Officer Martin, Fire Department Foreman Richard Filban, Fire Marshal George Dunlap, and the building's owner Horace Dean. There was deemed enough evidence to go to trial, and Kolakosky was bound over to Recorder's Court. He was arraigned on April 8th and charged with arson, to which he pleaded not guilty. The trial occurred on May 1st and he was acquitted by the jury. On May 18th, the Free Press noted: "After paying $125 attorneys' fees, and passing three months in jail, A. M. Kalokoski [sic] has settled with the insurance companies for $75."

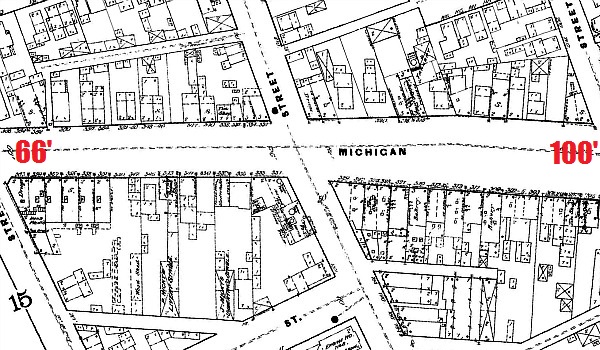

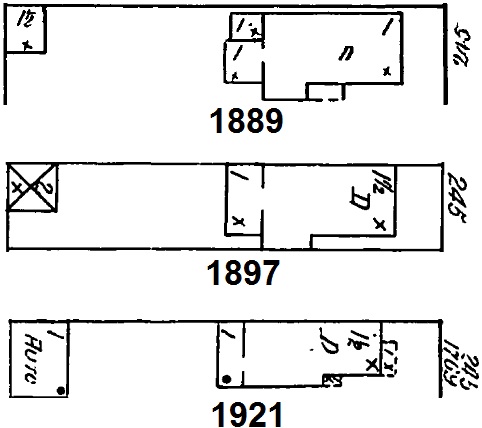

The block that includes 526 Michigan Avenue on the 1884 Sanborn map.

Other known occupants of this address:

| 1879-1880 | Geloramo Cannata, jeweler |

| 1881-1882 | William C. Wright, grocer |

| 1883 | Job Thomas & Co., grocers (Job Thomas & Alexander W. Slocum) |

| 1884 | Alfred G. Stanlake, grocer |

| 1885 | Holden & Westaway, grocers (Newton B. Holden & James Westaway) |

Newton B. Holden went missing on the night of April 24, 1885, having last been seen crossing the Detroit River in a rowboat. His parents lived in Sandwich (now Windsor), and crossing the river by this means was not uncommon. The boat was recovered from Grassy Island on May 1st, but Holden's body was not discovered until a month later, near Wyandotte. He had evidently drowned, but foul play was ruled out as his coat pockets still contained a large sum of money.

| 1885-1887 | Garrett Cotter, grocer |

| |

| 1888 | (Vacant) |

| 1889-1890 | Deubel & Voorhees, feed (William H. Deubel & George W. Voorhees) |

| 1891 | William S. Gill, harness maker |

| 1892 | James F. Walsh, upholsterer |

| 1893 | Singer Manufacturing Co., sewing machines |

For the next 36 years the space was used as a laundry establishment. In 1894 it was the Star Laundry, operated by Edgar C. Wheeler and Orra D. Pursell. The latter partner left the following year and the business was then run by Edgar C. Wheeler & Son from 1895 to 1905. By 1906 Star Laundry was acquired by Banner Laundry, a large, successful operation that had recently moved to the northwest corner of Brooklyn and Plum Streets, where it would thrive for decades. Their three-story headquarters still stands at 2233 Brooklyn and is now used as inexpensive lofts.

526 Michigan Avenue remained a laundry business until 1930, sometimes being listed as a branch location of Banner Laundry, sometimes as Star Laundry. In 1931 the space was used as storage for the National Upholstery and Furniture House, but after that it was vacant for much of the Great Depression.

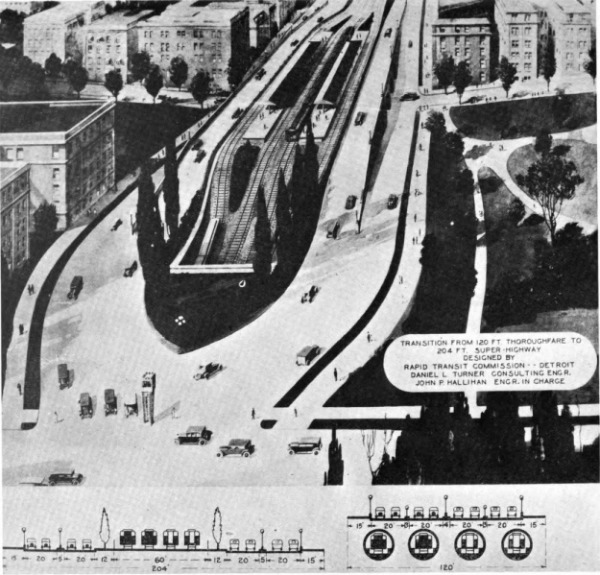

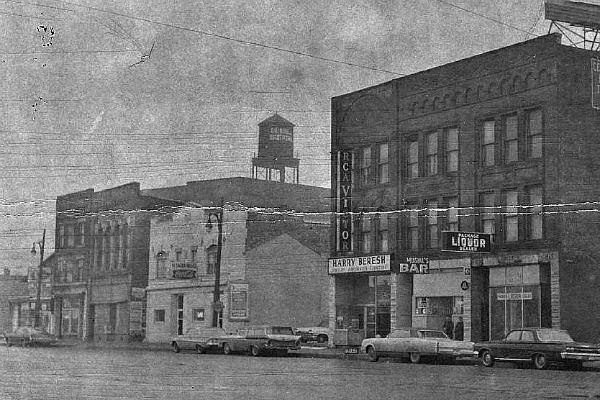

Michigan Avenue between Harrison and Cochrane, probably in the 1950s.

Courtesy Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

Other known tenants of this store (gaps do not necessarily indicate vacancy):

| 1938 | Wayne Home Improvement Co. (Samuel Pearlman) |

| 1939 | Harry Slotter Billiards |

| 1941 | Fit-Rite Glove Co. (Dermond St. Aubin & Gerald Doherty) |

| 1950-1955 | Michigan Glove Manufacturing Co. |

| 1961-1964 | Maltese-American Benevolent Society, Inc. |

| 1965-1975? | Central Billiards (Casimiro Nogueira) |

| 1975-1985 | The Hot Dog Place (Coney Island restaurant) |

1740-1744 Michigan Avenue in 1976.

Courtesy State Historic Preservation Office

In 1985, the family that owned The Hot Dog Place converted the restaurant into a sports memorabilia shop called The Designated Hatter. In 2000, it changed its name to The Detroit Athletic Company. It is now operated by brothers Steve and Dave Khalil, who started out selling peanuts and souvenirs to Tigers fans on the corner of Cochrane and Kaline Drive in 1982, when 1740 Michigan Avenue was still their father's restaurant. They acquired and expanded into the adjacent space in 1990.

528 (1744) Michigan Avenue

The other half of the Detroit Athletic Company's premises originally contained two commercial spaces--one that faced Michigan Avenue and one that faced Harrison.

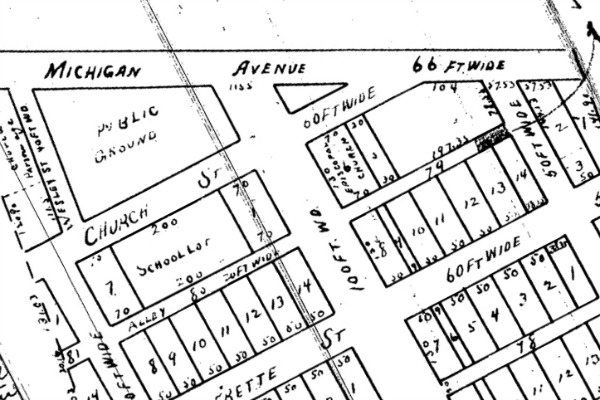

The Detroit Athletic Company block in the 1897 Sanborn map.

On August 26, 1890, building permit number 1305 was issued to the architecture firm Rogers and MacFarlane to construct a two-story brick store with an upstairs apartment at an estimated cost of $5,000. The firm was founded in 1885 by architects James S. Rogers and Walter MacFarlane. Their work includes the L. B. King & Co. Building on Library Street downtown.

A pharmacy run by William H. McFarland of the McFarland Brothers was the first commercial occupant of this space. The first store to bear the McFarland name was established by Andrew McFarland in 1880 just a few doors down at what is now 1700 Michigan Avenue. In a photograph very similar to the early 1880s near the top of this post, a painted sign for McFarland Brothers is partially visible on their first building:

Courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

An 1893 publication introducing the city to visitors describes the new McFarland Brothers location at 528 Michigan Avenue, which had opened two years before:

"Among the many pharmacies in Detroit, none is better managed than that of Mr. William McFarland, at the corner of Michigan and Harrison avenues... The store is elaborately finished in oak of modern design. The stock embraces everything in the way of drugs, fresh and pure chemicals, tinctures, elixirs, extracts, pharmaceutical, preparations of Mr. McFarland's own superior production, proprietary remedies, physicians' and surgeons' requisites, perfumery and a splendid array of toilet and fancy articles; also supplies for the sick rooms, and everything belonging to the business. The store is open at all hours of the day and night. The prescription department ... is supplied with every necessary appliance and is under the immediate supervision of Mr. McFarland."The photograph below is not of this store, but that of William's brother James McFarland on the corner of Fort Street and Campbell in 1894. Perhaps the Michigan Avenue location had a similar look and design to this one.

Courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

William McFarland operated the store at 528 Michigan Avenue until 1896. Another of his brothers, Lewis, took charge of this location until 1913.

Subsequent occupants included:

| 1914-1915 | John Paddock, drugs |

| 1916-1924 | James E. McEntee, drugs |

| 1925-1929 | Lynch Pharmacy (Charles V. Lynch) |

| 1930-1932 | Meriam Drug Co. (A. A. Meriam) |

| 1933 | Harrison Pharmacy (Charles A. Reed) |

| 1935-? | Mohmout Bros., groceries (Keder & Mehmet Mohmout) |

The Mohmout Brothers, from Turkey, operated a grocery store here until at least 1941, but the availability of city directories after the beginning of World War II is very inconsistent, and I can't say how long for sure they were at this location.

At least as early as 1956, Garcia's Groceries had set up shop at this address. The store, owned by John Solomon of Dearborn, specialized in imported Latin American foods. It operated at least through the 1970s.

2 (2226) Harrison Avenue

Two doors face Harrison Avenue--one to an upstairs apartment and the other to a small, triangle-shaped commercial space once addressed as 2 Harrison Avenue. From 1891 until 1915, it was a plumbing shop operated by John Kenealy Jr., who lived in the apartment above. His business was evidently very successful, as he had a two-story brick house built for himself and his wife behind the shop in 1903. Like the store, it was designed by architects Rogers & MacFarlane. Kenealy lived there until at least 1940, and possibly until his death in 1949. The home was demolished around 1990.

From 1916 to 1920, the Harrison store was rented by plumbers Keiran George Costello and Frederick William Abernethy. Costello had been an employee of Kenealy's for seventeen years prior to this business venture. In 1921 just Costello was listed at this address, which by then changed to 2226 Harrison. He was followed by electricians Frank Schroeder and Edward Charles Dygert in 1922.

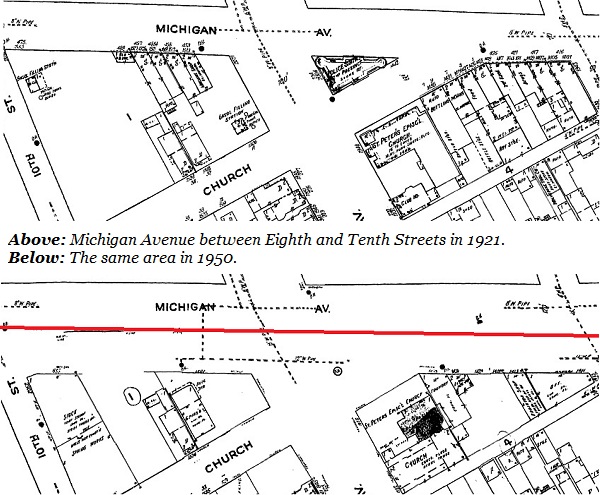

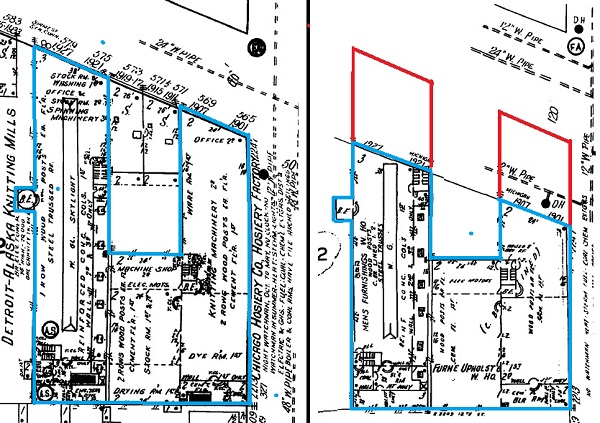

The Detroit Athletic Company block in the 1921 Sanborn map.

Beginning in 1923, this space became a cleaners operated by Albert and Louise Batty--in direct competition with the Star Laundry just two doors down. In fact, Mrs. Batty was the manager of the Star Laundry from 1920 to 1922. The Battys outlasted their competitor and were in operation until after Mr. Batty's death 1937.

Albert A. Batty, circa 1917.

Courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

In 1939 the Jewel Cleaners, operated by Lawrence Schwab, was at the address. It was followed by the Charles Cleaners, operated by Charles Youmans, beginning in 1940.

From 1979 to 1999, 2226 Harrison was the Corktown Social Club, founded by Ronald, Edward, and Douglas Herrick. The purpose of the organization, according to incorporation documents, was: "General pastime & drop in center for members consisting primarily of retirees, unemployed, & neighborhood residents to play games such as checkers, chess, dominos, pinochle, rummy, etc. or just plain fireside chats."

Today, 2226 Harrison and 1740 Michigan Avenue are used as storage and production space for the Detroit Athletic Company, whose showroom is located at 1744 Michigan Avenue. They are open to the public 10am to 5pm Monday through Saturday, and on Sundays during Tigers home games from 10am to game time.

Image Courtesy Detroit Athletic Company.