The story claims that the spoke-wheel layout of downtown Detroit is not the work of Augustus Woodward--who of course drew up a new plan for the city after it burned in 1805--but it was based on the Indian trails that converged in Campus Martius. "When Detroit was settled, Campus Martius was deemed the center of town because it was where all of these main roads came together," the author writes.

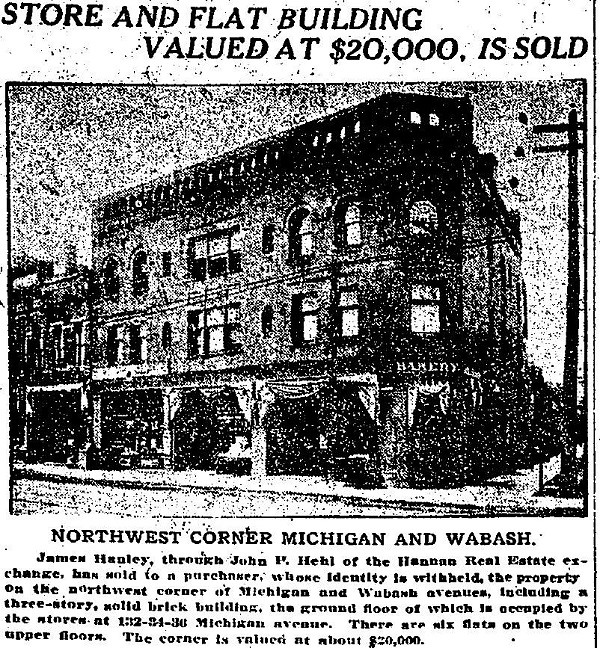

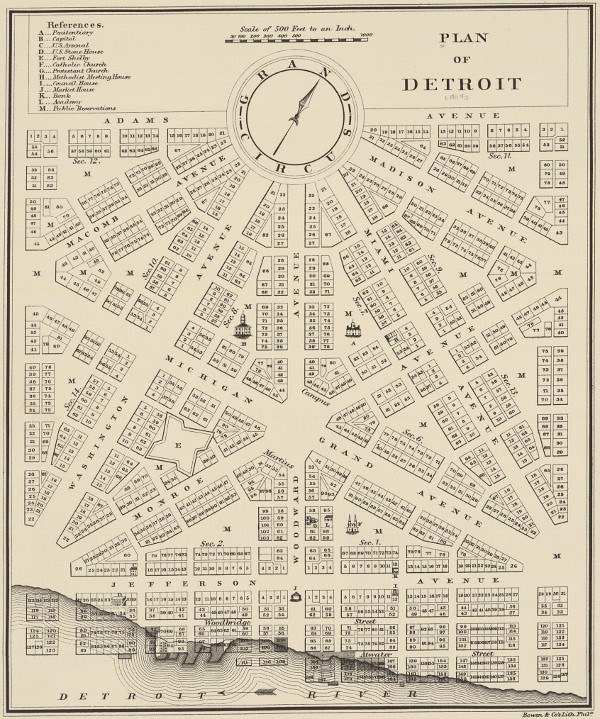

Campus Martius was not at all the center of early Detroit. The location of the original French fort was chosen for its defendability and convenience, not because of any confluence of Indian trails. There was not yet a settlement (European or Native American) for these trails to converge upon. Old Detroit stood at the water's edge near what is now the intersection of Jefferson Avenue and Shelby Street. The fort gradually grew until it reached about the size of four modern city blocks. In 1779, the British built a more modern military fort north of the old French town at what is now the intersection of Fort and Shelby Streets. Below is a map of Detroit from around 1796 (when the United States took over) with the city's modern street grid superimposed over it. Campus Martius, on the upper right hand corner, was well outside of the settlement.

Even as the city rebuilt following the 1805 fire, some Detroiters scoffed at the idea that the town would ever expand far enough to encompass what is now Campus Martius. John Gentle petitioned President Thomas Jefferson directly, complaining about taxes being wasted on "digging wells and erecting pumps ... near half a mile behind the town of Detroit, where in our opinion no town will ever exist." In the new town's early days, the greatest concentration of buildings was south of Jefferson Avenue, roughly where Hart Plaza is today. As late as 1819, the main streets of the town were Jefferson, Woodbridge, and Atwater, and the north-south streets barely even reached Campus Martius.

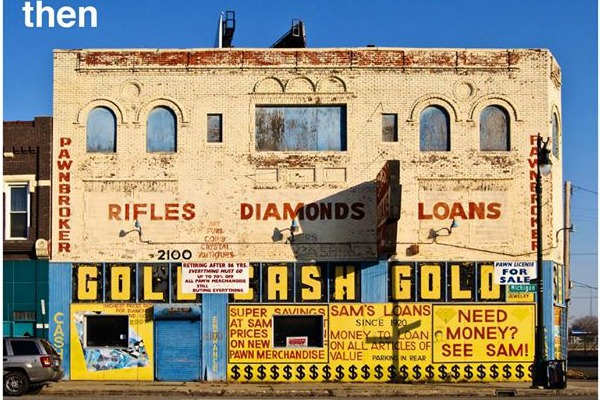

The conventional wisdom that the spoke-wheel street pattern of Detroit came from Augustus Woodward's ideas is actually correct. Here is one engraving of his magnificent plan:

The English-built fort, just west of Campus Martius, gives us a reference point for understanding its relation to the old settlement. Why did Woodward place Campus Martius, the center of the new city, where he did? It was simply because it was in the middle of the public grounds. Under French rule, none of the land immediately outside of the fort was ever granted to private individuals. It was surrounded by a large common area which was flanked on either side by privately owned ribbon farms.

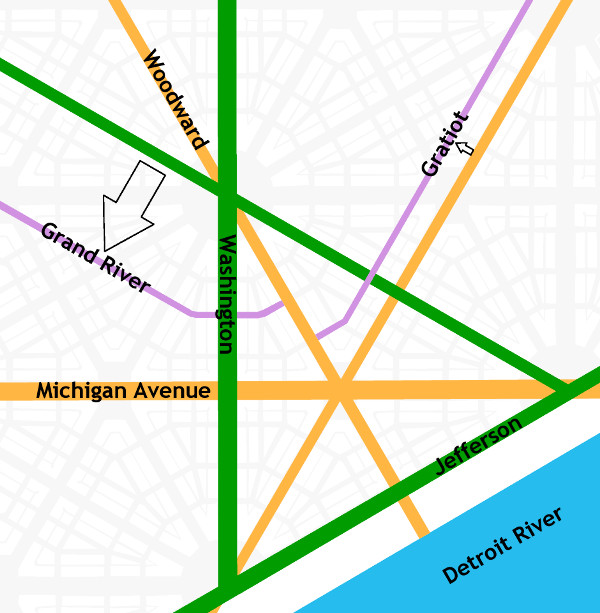

How do we know that our spoke-wheel roads are based on Woodward's plan? Let's look at how the plan is organized. Its foundation is a 4,000-foot equilateral triangle, outlined in green below. The triangle is bisected three times with streets (outlined in orange) that all intersect at Campus Martius.

Woodward's plan, if it was allowed to be fully carried out, would look like this, if the map is rotated so that due north is straight up:

The scheme viewed from farther out:

There are differences between this plan and the roads we have today, which I will get to in a moment. The point here is that these roads are all based on the bisected equilateral triangle, yielding avenues separated from one another by 30° angles. Indian trails followed the land, sticking to high ground, avoiding obstacles, crossing streams at their narrowest point. The roads built by the United States government cut straight, rigid paths through the land. Indian trails were unplanned, unmapped, and developed emergently under the feet of travelers following the most convenient route to a destination. They might branch out and reconnect, and did not have pinpoint beginnings and endings. Indian trails and Woodward's plan are two very different systems with very different origins.

How do today's roads diverge from Woodward's plan? First, Washington Avenue never continued north of Grand Circus Park. Second, Gratiot Avenue was built one block north of where it "should" have been because the owner of the Brush Farm had an orchard that was in the way. And third, Grand River Avenue didn't extend through Grand Circus Park from Miami Avenue (which is now named Broadway) but it is two blocks south of that. This is probably because Grand Circus Park was a swamp when construction began on Grand River Avenue in 1832.

Having said all that, didn't some of our roads begin as Indian trails? Definitely. US-24 between Detroit and Toledo mostly lies upon an old segment of the Maumee Trail, expanded and improved upon by the U.S. government in 1814. Much of the St. Joseph Trail is preserved by various rural highways. Shiawassee Road in Farmington coincides with an Indian trail that appears in an 1817 survey:

If I do make one concession to the idea that Woodward's plan is connected to the Indian trails, it would be to say that Woodward Avenue did replace the old Saginaw Trail between Detroit and Pontiac. This path appears on an 1817 survey of Royal Oak Township (which was once a six-mile-by-six-mile square bound by 8 Mile Rd., Dequindre, 14 Mile Rd., and Greenfield). Here is that path (which splits into two and then comes together again) superimposed over a modern map of the area:

When you are driving on Woodward Avenue in Detroit, you aren't exactly retracing the steps of the Native Americans and pioneers of two centuries ago, but you are at least headed in approximately the same direction.

It is claimed that Michigan Avenue (US-12) follows the Sauk Trail. This is true for much of US-12 in the middle of the state, but it is not true of Michigan Avenue within today's Detroit city limits. Michigan Avenue begins at Campus Martius and heads in a straight line due west for almost five miles before turning south to eventually meet the old Indian path many miles later. Most likely, it appears that eastbound travelers on the Sauk Trail came to Detroit by first arriving at the River Raisin, following it down to the Detroit River, and then following the shoreline upstream to Detroit.

Some say that Gratiot Avenue follows the old Moravian Road, but that is not correct. The Moravian Road actually began at Connor's Creek, 4.5 miles east of Campus Martius. It curved to the northeast and ended at the Moravians' settlement in what is now Harrison Township. Gratiot Avenue begins in downtown Detroit, runs in a straight line for fifteen miles before its first curve, and terminates in Port Huron. These roads head in roughly the same direction, but one is not based on the other.

Detroit and vicinity circa 1797.

Source: King, Robert after Patrick McNiff. A Rough Sketch of part of Wayne County Territory of theUnited States North-west of the River Ohio [map]. In: Dunnigan, Brian L. Frontier Metropolis: Picturing Early Detroit, 1701-1838. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2001, p. 106.

Grand River Avenue has a similar story to Michigan Avenue. It is often claimed to be an Indian trail, but that is only true for some portions well within the interior of the state. It began as a road to Howell before being extended to the west side of Michigan. Perhaps it is confused with the Shiawassee trail, which intersected Grand River Avenue in downtown Farmington. This trail appears to begin well west of the settlement at Detroit, and heads north to Saginaw after passing through Farmington.

Detail from an 1825 survey of Michigan, showing the Shiawassee Trail. (Source.)

There is SO MUCH MORE that I wish I could write about. I didn't even mention the Woodward plan's Point of Origin, which you can see in Campus Martius Park; or the amazing Public Land Survey System; or the beautiful connection between the two, or their relationship to 8 Mile Road (which, by the way, has nothing to do with the Wisconsin/Illinois border as the article also claims).

Thank you, Michigan Radio, for bringing up my favorite subject! Honestly, this has made me want to start a whole new blog just about the urban planning history of Detroit.